Depending on geographical location, Pagans had various beliefs and rituals that centered around a polytheistic religion that focused on components such as nature and the natural world and ancestral worship. The Germanic tribes that emigrated to England often shared similar beliefs and some specific Gods as Norse Paganism such as Woden or Odin and Thor, Thunor, or Donar. Germanic Paganism (which is often referred to “Anglo-Saxon” Paganism although as discussed in this website, does not accurately refer to the Germanic tribes) did not have written texts and much of the historical record of what is known is of Christian primary source information. While the Roman pantheon had gods for specified aspects of nature, such as Mars who was the god of war, Pagan gods were in charge of a multitude of natural things. Germanic Paganism believed Thunor was the god of thunder as well as a god of fertility. From sources like Snorri’s Edda, in Norse mythology, Thunor, who was known as Thor, has a similar capacity and was the god of thunder as well as the god of good harvest, and the god of hallowing (or to make things holy).

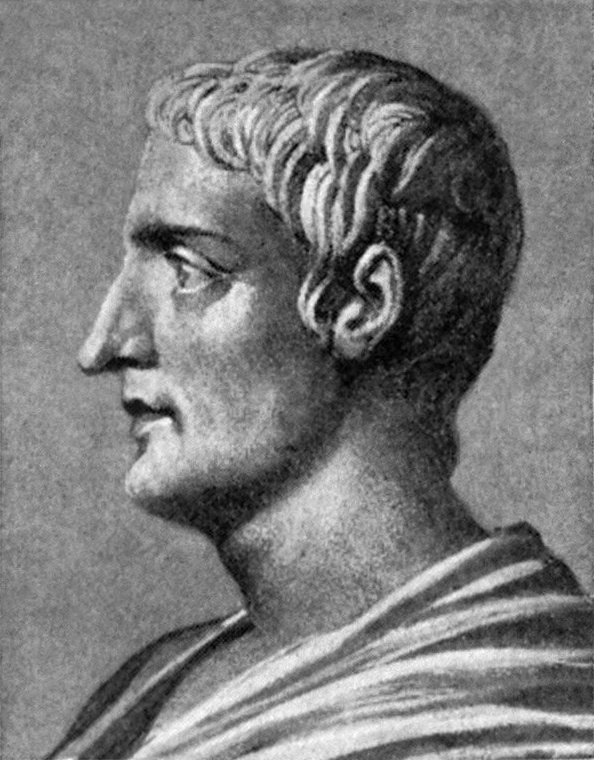

When Roman historian, Tacitus, wrote Germania around 98AD, he discussed the belief system of the Germanic peoples the Romans encountered. Tacitus notes the differences and similarities between the German religion and that of his own people, the Romans. He writes, “They have a tradition that Hercules also had been in their country, and him above all other heroes they extol in their songs when they advance to battle.” Throughout Germania, there are many similarities in the gods believed in by the Germanic people that are reminiscent of the Roman pantheon. Tacitus recounts how the Germanic people also worshipped Mercury, he writes, “Of all the Gods, Mercury is he whom they worship most.” While he states the similarity in belief of Mercury, Tacitus also notes the ritual of human and animal sacrifice practiced, unlike the Romans. Human sacrifice is a common ritual between various religious belief systems of the time; the Druids of Gaul, later Celtic Druids, also practiced human and animal sacrifice. Tacitus dictates that these sacrifices were made to satisfy Mercury and Mars, two gods whom they worshipped, similar to the Romans. It is apparent that the Germanic Pagans shared beliefs that were also held by other polytheistic religions such as that of the Romans and of Scandinavian peoples.

Julius Caesar’s account of the Druids is the main primary source information on their religious practices and beliefs as they, like the Germanic Pagans, did not keep written records. As archaeologist Miranda Aldhouse-Green writes in her book, Caesar’s Druids: Story of an Ancient Priesthood, “Gaius Julius Caesar is our richest textual source for ancient Druids and he is also one of the most reliable.” Caesar’s account of the Druids portrays them as an established society that were the governing body of their community, imposed religious sanctions, and ordained and organized rituals such as human and animal sacrifice. When researching both the Germanic Pagans who later emigrated to England as well as the Celtic Druids, it is apparent that they were an established religion with rich cultural history. Despite the lack of written records by both groups, from observations such as those by Tacitus, the Germanic tribes were not “heathens” or “barbarians” but coordinated and organized peoples. The societal organization of Germanic Pagans has defined by monarchies; kings presided over their lands and ruled their subjects. In a portion of Germania referring to religious practices, Tacitus writes, “They worship the Mother of the Gods. As the characteristic of their national superstition, they wear the images of wild boars. This alone serves them for arms, this is the safeguard of all, and by this every worshipper of the goddess is secured even amidst his foes.” He later goes on to say, “But, according to the ordinary incuriosity and ignorance of Barbarians, they have neither learnt, nor do they inquire, what is its nature, or from what cause it is produced.” When reading these primary source documents on either the Germanic Pagans or the Druids, it is obvious that they were written through the biased lens of the author; in this case, Tacitus, who believed the Roman polytheistic religion and culture to be superior than that of the Germanic Pagans.

Druids believed in the concept of a “soul,” and taught that each person possessed a soul that could not die (an immortal soul). Druids used divination were thought to be able to foretell the will of the Gods. Tacitus also wrote on the heavy reliance on divination believed by the Germanic Pagans. He wrote, “Their method of divining by lots is exceeding simple. From a tree which bears fruit they cut a twig, and divide it into two small pieces. These they distinguish by so many several marks, and throw them at random and without order upon a white garment. Then the Priest of the community, if for the public the lots are consulted, or the father of a family if about a private concern, after he has solemnly invoked the Gods, with eyes lifted up to heaven, takes up every piece thrice, and having done thus forms a judgment according to the marks before made.” Divination was also used by the Romans in understanding the will of the Gods but the Pagans utilized nature to understand the will of their gods or goddesses. Druids also acted as teachers, judges, as well as controlling religious rituals such as sacrifices. The Druid leaders also had the power to ban whomever they wanted from attending sacrifices, the only group within a community who could do so, as said by Caesar on his observations of their religious practices. Druids relied upon nature to provide them with signs from the gods, such as listening to the sounds made by birds or the observation of the formation of clouds.

Historians emphasize the importance of Woden to Pagans of England who claimed to trace their lineage back to Woden and were able to certify their rule through divine descent. Historian William Chaney asserts that a “Woden cult” worship existed within the various kings of England. He writes, “But of more importance to us is the assimilation of his cult to the new religion, since the culture of Woden-sprung Kings and Woden-worship did not allow the name or the cult to perish.” With the entrance of Christianity to England, Woden did not simply disappear. The name “Wednesday” comes from “Woden’s Day” which was associated with the Christian devil. Woden in other iterations, according to some scholars, was absorbed into the Christian religion as a form of God. As written in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, “Their leaders were two brothers, Hengest and Horsa; who were the sons of Wihtgils; Wihtgils was the son of Witta, Witta of Wecta, Wecta of Woden. From this Woden arose all our royal kindred, and that of the Southumbrians also.” Although some scholars argue over the importance of Woden in England, others assert that his presence permeated England, as made apparent by multiple locations named after Woden. Historian A.L. Meaney asserts while arguing with another historian’s claims in his article, “They are rather more frequent than Mr. Ryan indicates, numbering eleven as at the present known. Four have a second element meaning ‘hill, barrow’: Woodnesborough, Kent (near which were found thirty Anglo-Saxon glass vessels), and Wodnesbeorh, the old name for Adam’s Grave Wilts., are combined with Old Engligh beorh.” The Woden “cult” can be surmised by historians to retain popularity even post-conversion based on the naming of various geographic locations around England named after him. While Christians may have sought to rename these locations, they maintained their Pagan based names.